Shopping is a core activity in the life of most Australians. As such, it can be argued that the nature of the shopping experience can impact on people’s broader quality of life.

The negative side of compulsive shopping is well documented in social research, as well as in popular culture: Isla Fisher’s character in Confessions of a Shopaholic, for example, manages to almost ruin her life through her addiction to purchasing fashion she can’t afford.

But what of the positive aspects? Can shopping improve people’s wellbeing?

We’re familiar with this notion through catch phrases like ‘retail therapy’, but shopping is more than just buying things – especially in sophisticated modern retail environments. It also includes social, community and leisure aspects of life, which are all part of the shopping experience.

Recent North-American research argues that satisfaction of these life areas contributes to overall feelings of wellbeing among consumers. This satisfaction is tied up with the features of the shopping centre – its functionality, convenience, safety, leisure, atmospherics, and consumers’ self-identification with it.

The researchers found that high levels of satisfaction with the shopping environment on these sorts of attributes translated to higher levels of shopper wellbeing (that is, general life enjoyment and satisfaction). When we combine this with other recent evidence that shopping itself really does make us happy, it suggests that creating great retail environments is not only good business practice, but positively contributes to the lives of the people who patronise our shopping centres.

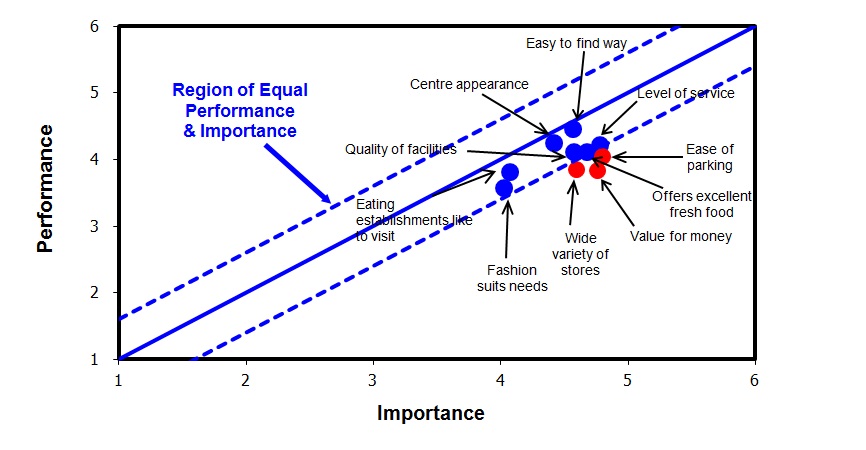

One of the things we regularly test when conducting consumer research in shopping centres is how customers rank different attributes of a centre. One way to graphically represent whether a centre is meeting customer expectations is to then map the importance customers assign to particular attributes against the performance of the centre on these attributes. This produces a gap analysis.

Figure 1 provides a gap analysis of importance and performance ratings of 10 attributes across all shopping centre types in Australia (from a sample of 26,000 interviews). In this example we see that

three attributes (the red dots) fall outside the region of equal importance and performance: value for money; wide variety of stores; and ease of parking.

This tells us some things we already know: that consumers are exceptionally price conscious, that there are issues with homogenisation across shopping centres and that parking is a perennial bugbear with shoppers.

At an individual centre level, though, there will be more diversity in both the expectations of customers and the performance of a centre. Measuring these provides insight into the strength of your centre’s positioning in its trade area.

Meeting customer expectations through performing on these attributes contributes directly to levels of patronage, expenditure, and customer loyalty. But the international research discussed earlier also demonstrates that there is a positive community aspect to providing quality shopping centre environments and that by creating such spaces, companies are engaging in a form of corporate citizenship (even as they grow profits).

International academic research cited in this article can be found in: Kamel El Hedhli, Jean-Charles Chebat, M. Joseph Sirgy, ‘Shopping well-being at the mall: Construct, antecedents, and consequences’, Journal of Business Research, 66 (2013): pp. 856–863.